From the Desk of Dan Brooks ―

The Second Circuit’s recent Andy Warhol fair use decision attempts to clarify its Cariou standard, which remains conclusory and continues not to offer meaningful guidance or predictability.

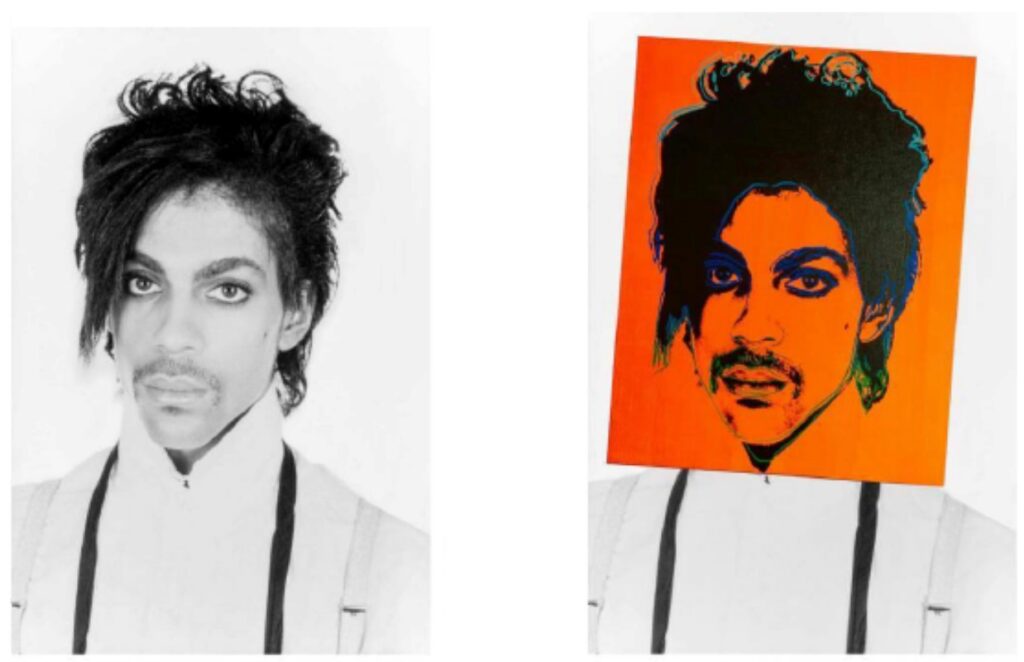

In a recent high-profile decision, the Second Circuit held that iconic vividly colored Andy Warhol silkscreens made from a copyrighted black and white photograph of the musical artist Prince were not “transformative” and could not be defended as fair use by the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts. Andy Warhol Found. for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, ___ F.3d ___, 2021 WL 1148826 (2d Cir. Mar. 26, 2021). The original black and white photograph, taken by photographer Lynn Goldsmith, and one of the series of Warhol silkscreens (the Orange Prince) look like this:

The district court had ruled, based on a Second Circuit precedent, Cariou v. Prince, 714 F.3d 694 (2d Cir. 2013), that the Warhol silkscreens were transformative (and constituted fair use) because the original photograph had been altered to create a new aesthetic. Warhol Foundation, 2021 WL 1148826, at *5. In reversing the district court, the Warhol Foundation panel noted that Cariou had been described, in an intervening Second Circuit decision, as the “high-water mark of our court’s recognition of transformative works.” Id. (quoting TCA Television Corp. v. McCollum, 839 F.3d 168, 181 (2d Cir. 2016)). Citing TCA Television, the Warhol Foundation Court also acknowledged that Cariou had received criticism from a sister circuit and from a leading commentator. Warhol Foundation, at *5. Specifically, as cited in TCA, 839 F.3d at 181, in Kienitz v. Sconnie Nation LLC, 766 F.3d 756, 758 (7th Cir. 2014), the Seventh Circuit, recognizing that a copyright owner has the exclusive right to prepare derivative works, which by statutory definition are transformative, pointed out that: “to say that a new use transforms the work is precisely to say that it is derivative and thus, one might suppose, protected under § 106(2). Cariou and its predecessors in the Second Circuit do not explain how every ‘transformative use’ can be ‘fair use’ without extinguishing the author’s rights under § 106(2) [the derivative works right].” Similarly, TCA quoted Nimmer’s criticism of Cariou: “It would seem that the pendulum has swung too far in the direction of recognizing any alteration as transformative, such that this doctrine now threatens to swallow fair use.” TCA, 839 F.3d at 181, quoting 4 Melville Nimmer & David Nimmer, Nimmer on Copyright, § 13.05[B][6], at 13.224.20.

Acknowledging these criticisms, the Warhol Foundation panel stated: “While we remain bound by Cariou, and have no occasion or desire to question its correctness on its own facts, our review of the decision below persuades us that some clarification is in order.” Warhol Foundation, at *5. As counsel for plaintiff Patrick Cariou in the Cariou case, it is this attempted clarification that is of particular interest to me.

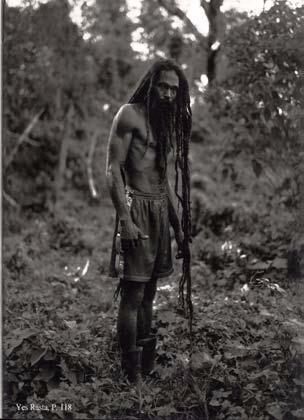

The Court observed that Cariou involved thirty paintings by the contemporary visual artist Richard Prince (no relation, obviously, to the musical artist Prince whose image was the focus of the Andy Warhol silkscreens) that appropriated images from Patrick Cariou’s book, Yes Rasta, consisting of black and white portraits of Rastafarians in Jamaica and images of the landscapes in which they lived. Id. The majority opinion in Cariou held that, as a matter of law, 25 of the paintings were transformative and constituted fair use. Cariou, 714 F.3d at 711. The case was remanded, however, to the district court for further proceedings because the Cariou majority could not “confidently . . . make a determination about [the] true nature [of the five remaining paintings] as a matter of law.” Id.

The Warhol Foundation Court sought to clarify Cariou by explaining that the 25 paintings that were deemed transformative as a matter of law differed from the five paintings that were the subject of the remand to the district court for a determination of transformativeness. The Court concluded that, in the paintings found to be transformative as a matter of law, the original photo was juxtaposed with other photos and “obscured and altered to the point that Cariou’s original [was] barely recognizable.” Warhol Foundation, at *7, quoting Cariou, 714 F.3d at 710.[1] According to the Warhol Foundation Court, in the five potentially infringing paintings in Cariou, the original “was altered in ways that did not incorporate other images and that superimposed other elements that did not obscure the original image and in which the original image remained . . . a major if not dominant component of the impression created by the allegedly infringing work.” Warhol Foundation, at *7. Applying this distinction, the Warhol Foundation Court found that the Warhol silkscreens were not transformative because they retained the essential elements of the original Goldsmith photo of Prince. Id. at *9.

The distinction posited by the Warhol Foundation Court is anomalous because fair use normally illuminates, rather than obscures, an original work, as can be seen by the preambular examples of fair use in the statute, 17 U.S.C. § 107 (purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, or research, all of which shed light on the original.) The purported distinction is also at odds with the actual images in Cariou.

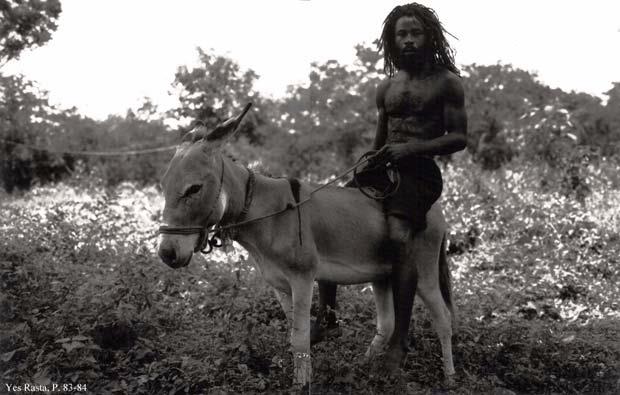

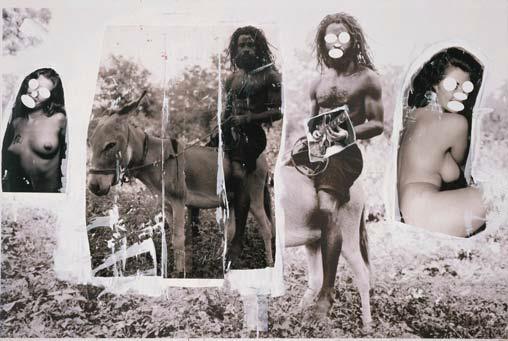

One of the photographs in Yes Rasta, depicting a Rastafarian man riding a burro, was used in two of the Richard Prince paintings, Back to the Garden (which was found to be transformative as a matter of law) and Charlie Company (which was one of the five paintings which were the subject of the remand to the district court). Here are the three images:

Clearly, Cariou’s original photograph is no more obscured or unrecognizable in Back to the Garden than it is in Charlie Company, both of which incorporate other images. Indeed, in Back to the Garden, one of the images of the Rastafarian in Cariou’s original photograph is completely unobscured, lacking the painted lozenges that cover part of his face in all the images in Charlie Company. The Rastafarian on the burro is a major if not dominant component of both paintings and the other images juxtaposed with the Cariou image (primarily nude women) are quite similar in both paintings and do not obscure or supplant Cariou’s original photograph. There simply is no objective reason why Back to the Garden, but not Charlie Company, should be deemed transformative and fair use as a matter of law.

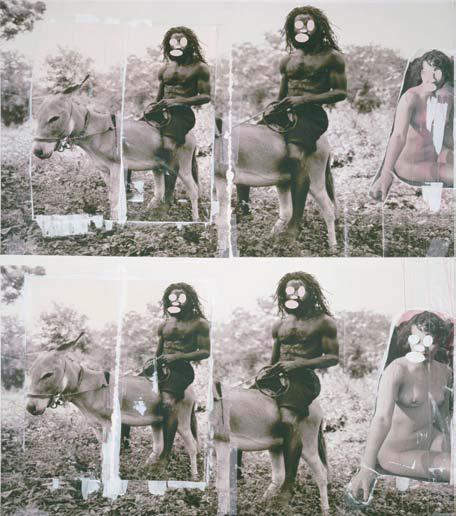

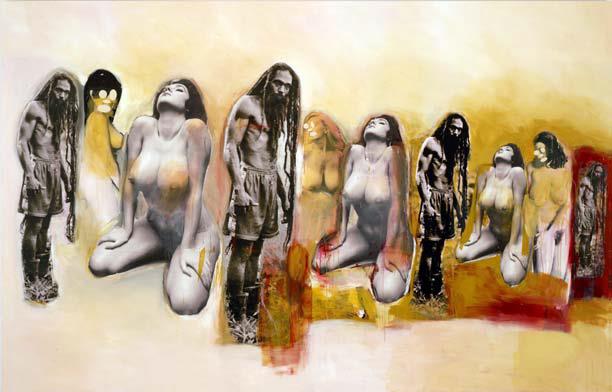

Another example is provided by a Cariou photograph of a Rastafarian standing near a clearing in a forest and two Richard Prince paintings incorporating that image: Tales of Brave Ulysses (transformative as a matter of law according to the Cariou majority opinion) and Graduation (one of the five remanded paintings). Here are those three images:

Cariou’s original figure is a major and unobscured component of both paintings. In Tales of Brave Ulysses, the Cariou image, which is reproduced four times, is surrounded but not obscured by naked women and lacks any painted lozenges on his face, whereas, in Graduation, the man’s face has painted lozenges partially hiding his features and he is holding a blue guitar, which alters his pose and creates a different aesthetic. Yet, it was Tales of Brave Ulysses but not Graduation which the majority found to be transformative as a matter of law.

There is no principled distinction separating these paintings in terms of transformativeness. Instead, the Second Circuit’s fair use cases appear to depend for their outcome upon the subjective views of the judges randomly selected to preside over them – a standard which offers predictability neither to copyright owners nor to secondary users. To paraphrase Justice Stewart’s famous dictum, when it comes to transformativeness, those judges think they “know it when [they] see it.” Jacobellis v. Ohio, 378 U.S. 184, 197 (1964) (Stewart, J., concurring). Or, as Nimmer put it, applications of the transformative use standard are “conclusory – they appear to label a use ‘not transformative’ as a shorthand for ‘not fair,’ and correlatively ‘transformative’ for ‘fair.’ Such a strategy empties the term of meaning – for the ‘transformative’ moniker to guide, rather than follow, the fair use analysis, it must amount to more than a conclusory label. As one commentator laments, ‘the transformative standard has become all things to all people.’” Nimmer on Copyright, § 13.05[A][1][b], at 13-170.

The Cariou standard does not require clarification. Instead, it should be jettisoned and replaced with an analysis which permits the unauthorized use of copyrighted images only when the particular use is justified and does not unfairly exploit creators of easily appropriated materials, such as photographers. Whatever the precise contours of such a standard, it cannot rely on the subjective whims of randomly assigned judges. “‘It would be a dangerous undertaking for persons trained only in the law to constitute themselves final judges of the worth of pictorial illustrations, outside of the narrowest and most obvious limits.’” Warhol Foundation, at *8, quoting Bleistein v. Donaldson Lithographing Co., 188 U.S. 239, 251 (1903) (Holmes, J.)

[1] Left unexplained was what fair use justification could possibly exist for appropriating a particular copyrighted work in order to obscure and alter it to the point of rendering it unrecognizable. Cf. Pierre N. Leval, Toward a Fair Use Standard, 103 Harv. L. Rev. 1105, 1111 (1990) (the first fair use factor, the purpose and character of the use, “raises the question of justification.”)